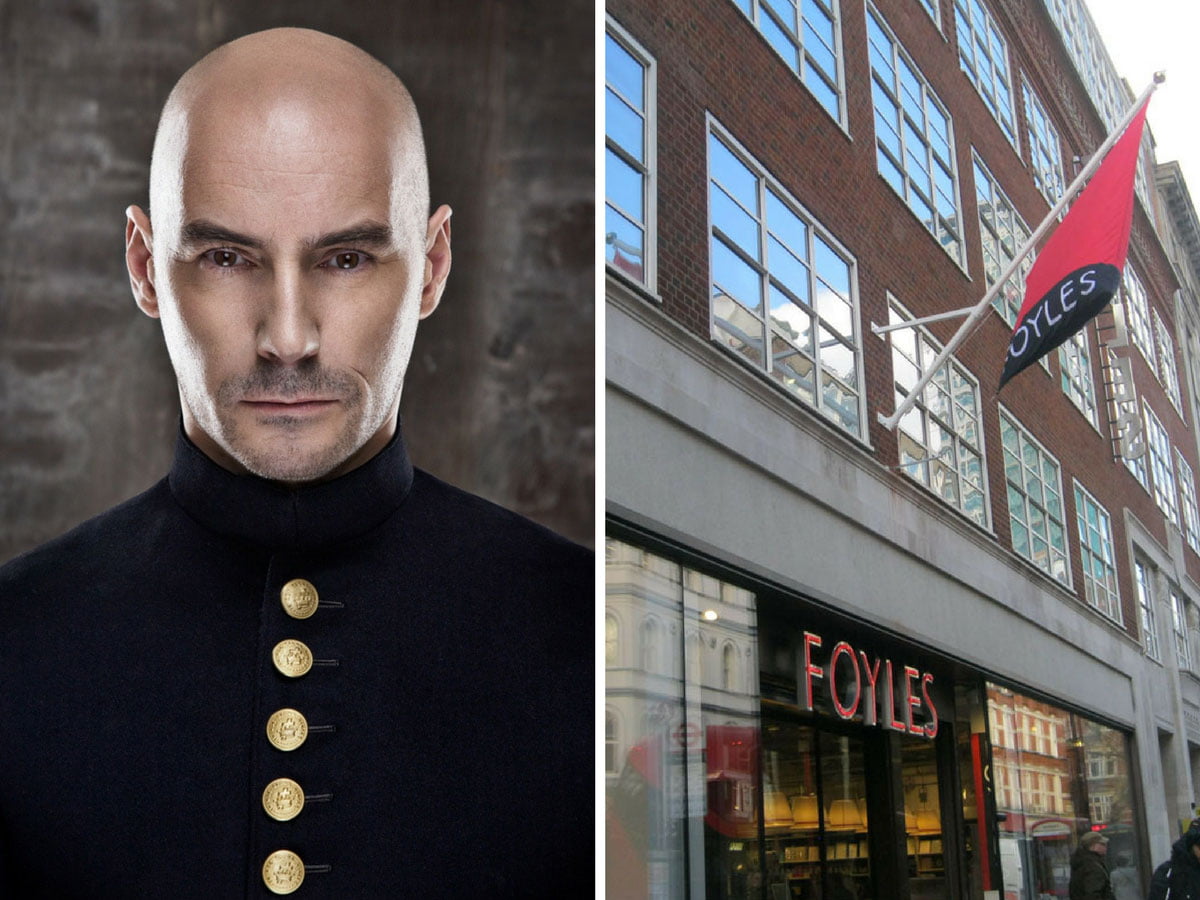

Grant Morrison participated in a Q&A in Foyles on Charing Cross Road on Tuesday evening to promote his new book, Supergods. Because we were not allowed to photograph or record the Q&A, these are my long and rambling recollections of the hour.

I was lucky to get tickets for this event – The Gallery on the third floor of Foyles on Charing Cross Road was full of Grant Morrison fans (all seats were taken, people were standing up; among the crowd, I spotted the new chap from Gosh!, and Bleeding Cool’s Rich Johnston was present of course, and there was a chap who had some original artwork from Grant Morrison’s Animal Man, which I assume he was going to have signed afterwards). I had a nervous moment when the woman with the clipboard of power had to flip to the third page before she found my name on the list, but find it she did and I took my seat in the third row on the left of a small aisle in the main bulk of seats. This was a good choice – it meant that I had a perfect view of the God of All Comics.

Grant Morrison was looking in good shape – no shiny white suit, rather a dark blazer, a dark t-shirt with a design and slogan on it and shiny black trousers, to contrast his bright shaven head – and he seemed happy and comfortable as he sat down to begin the hour of Q&A to promote his new book, Supergods. As he drunk from his glass, he commented how much it looked like a urine sample: ‘Mmm, Neil Armstrong.’ Laughter would be a regular background noise throughout. After the clip-on microphones had to be replaced with an old-fashioned microphone (Morrison started crooning Strangers In The Night when it was passed to him), things were got underway. He explained how the book came about: an editor friend suggested compiling his interviews (great, thought Morrison, 500 pages and I don’t have to do anything); Morrison’s agent suggested he write a new introduction; when the agent read the introduction, he said, ‘This is good, why don’t you write a book?’ This was at a time when Morrison was in the middle of Final Crisis and Batman: RIP, so it’s not as if he wasn’t busy enough already. However, he couldn’t turn down the opportunity to create a ‘cultural artefact’ when given the opportunity; 18 months later, he wasn’t feeling the same way – he described clinging to his desk, having worked ridiculously long hours and avoiding friends, leading to what he called a ‘businessman’s breakdown’, where he would stop because he simply couldn’t continue but 15 minutes later would knuckle down and get back to work because he ‘had to’. Despite this, he’s very happy with how it turned out and that it exists.

(My recall of the specific timeline of questions and answers after this first round of discussion is a little hazy, and the phrasing might not match the exact words used by Morrison, so please allow for some interpretation.)

Morrison talked about the ‘superheroes as archetypes’ idea (Superman is Zeus, Batman is Hades) but he expanded on it – Flash is Hermes and the Egyptian Isis and the Babylonian Nabu (god of wisdom and writing), but now Flash represents more than just that: he is the idea of modernity, of modern-day communication, of fashion, of transformation. Morrison’s depth of understanding and his ability to explain it is quite breath-taking – he is a smart man who has obviously thought about this a great deal and what it means to him personally. The point of archetypes is more than just the superheroes, it’s about ideas – he talked about the idea of love existing throughout human existence (we all hope to experience it at some stage, but the idea of love remains whether we do or not), or the idea of anger (which was represented as the ultimate form of anger in gods of war), or the idea of being 16 (we all experience it but only for a year, but there is always someone somewhere who is intense feeling of being 16). I was smiling just listening him drop knowledge bombs on his attentive audience.

The book examines the relevance of the lightning symbol in the development of the comic book, and Morrison discussed some aspects of it. The lightning bolt is present throughout the ages of comics, from Captain Marvel in the Golden Age, through the Flash in the Silver Age, Alan Moore’s Marvelman (a version of Captain Marvel, don’t forget) in what Morrison terms the Dark Age (from the mid-1970s to the early 1990s), and the Flash again in Mark Waid’s run on the character, which Morrison sees as the start of the current renaissance of comics. In the book, he links this to the Kabbalah (the original version, not the string-wearing modern silliness) and the magician’s path – the jagged structure from right to left (which is the reverse in the Reverse Flash, which reflects the dark magician’s path) – and he tried to put this structure into the book itself

He talked about the notorious alien abduction episode – where he was taken up by aliens on a higher dimension and they reassured him about the state of the world – about the different branes of reality, describing it terms of how we can see lives represented in 2D in comics, so what if there are beings on a dimension who can see us in the same manner of higher dimensions because they can see five dimensions, including time, so they can read us in the same way we read comics, seeing us at all points of our life at the same time. He also says that, regarding the abduction, he doesn’t believe it, but he does (with a cheeky grin on his face) – it’s a fiction but a really positive fiction

One topic that recurred was the concept of the reality of superhero comics. For example, Superman is more real than us – he’s been around for longer, he will be around long after we are dead, more people know who he is than will ever know. Morrison talked about how adults (a pejorative term for people who have closed minds who can’t enjoy themselves) don’t get fiction, particularly superheroes – they can’t enjoy the comics because they let reality intrude (how can Bruce Wayne run a billion-dollar business during the day and be the Batman at night? It’s not possible. To which Grant responds, with an unbelieving smirk on his lips, ‘because he’s not real’). In contrast, children understand the difference between fiction and reality, despite what adults think, and don’t believe that a cartoon of a crab is the same thing as an actual crab and don’t expect them to start singing and dancing.

Another facet of this the participation of the real world in comic books: the original Superman and Batman were realistic superheroes – they were responses to world around them, facing foes from headlines – whereas Captain Marvel was the first magical hero, with the mythic origin. He expanded on this by providing his thoughts on the types of writers of superheroes. He believes there are two types: the Missionary and the Anthropologist. The Missionary comes along and imposes his reality on a character: in real life, the missionary arrives at a new civilisation and says, ‘you’re naked, here’s a Bible, you’re doing everything wrong’ (despite the fact that the civilisation was fine before they came along); in his analogy, this leads to comics that are realistic and dependent on the outside world to impose rules on the stories. In contrast, the Anthropologist takes a different approach: when an anthropologist meets a new society, he strips down, paints his face, eats food he shouldn’t, blends in, gets stuck in and accepts their customs; his Anthropologist writer accepts the rules and limitless imagination of superheroes and works with them to come up with something new. Obviously, Morrison sees himself as the Anthropologist, who believes in the unreal reality of the superhero and enjoys it and celebrates it and doesn’t impose the real world on the superhero (or, as he put it, ‘Batman has never pissed EVER because he’s not real’ – take that, Kevin Smith). Saying that, he did state, ‘Watchmen is a beautifully written piece of work, you can’t take anything away from it’, despite it being an obvious example of the reality-based superhero story.

I can’t remember the context for the next answer but it had a lovely feel to it: for Morrison, writing superhero comics is like twelve-bar blues – there is a basic structure to it but with that you can do anything you want as long as you stay within the parameters of the rules. The analogy of someone who knows what he is doing and talking about.

Morrison was specifically asked about Action Comics, his new book about Superman in the new DC universe in September – in the book, Morrison wants to address certain issues that ‘adults’ have about the character, but he’s not allowed to say anything about it because of signed NDAs.

After 30 minutes, the Q&A was opened up to questions from the audience. I captured some of them, although I can’t always remember the questions. There is more Seaguy coming (Morrison thinks it is the best thing he’s written). When asked about the conspiracy stuff of his Invisibles, he agrees that there are no lizards running everything because we humans are not smart enough yet, so the world is all chaos. When asked about his first experience with superheroes, he said that he learned to read at three years old (thanks to his mother), and that his first comic was a story where Marvelman meets Baron Munchausen (which obviously influenced everything he’s done since, because it is the story of a magical superhero meeting a complete liar). He talked about how his parents were anti-bomb activists, which affected him a lot as a kid, not helped by the family friends would sing songs about the bomb, so he was really worried about the bomb. The arrival of superheroes was exactly what he needed because these characters could defy the bomb and diffuse his fears.

When asked about the contradiction between believing in the reality of the DC universe, which exists outside the people who have created it, and the reality of the fact the DC universe is owned by a corporation, he said that nobody owns superheroes – we do, everybody does, like Robin Hood or King Arthur – and that they will probably soon be open source soon and we will all be writing these characters. On a related note, he said that he doesn’t have carte blanche at DC, he is just allowed to do his stuff because his comics sell. When talking about comic books in general, he professed that he mostly loves superheroes rather than comics as a medium – he isn’t interested in, say, a comic from a bloke in Iran. Related to his Missionary/Anthropologist analogy, he explained quite succinctly the difference between stories that are relevant to the world around us and those from the imagination – he wants stories that are ripped from the neurones, not the headlines.

Morrison loves the ways comics engage both sides of the brain simultaneously, and he is undecided about digital comics – at the moment, he thinks they are like early cinema trying to recreate theatre, that they are just replicating comic books on another medium, even as far as having you flip the pages – and is waiting to see the development because of its potential; he’d like to see digital comics where you can press on a character and the entire history of the character would pop up, or press on another part of the page and you could play a related game. Asked about the way that Batman is being reset to only Bruce Wayne in the new DC and how he felt about DC ignoring his Batman stories, he said he knew it was never going to last, which is why he always tries to write a complete story in his entire run on a book (such as on Batman and New X-Men) that reflects his passions and affection for the characters, because the characters will always be reverted to the status quo.

Morrison talked about something he discusses in his book, which is the superhero history in terms of a life: Golden Age is like a child, with its simplicity and bright colours and black and white viewpoint; Silver Age is 12 years old, the age of transformation, as puberty hits and there are lots of changes (such as Superman becoming fat/multiple/small, or Flash and his large head/gorilla, or Jimmy Olsen and his many changes); Dark Age is adolescence, with its anger towards the previous way of doing things, making things more serious; current Age is adult, intelligent and knowing but also playful (he used Warren Ellis’ work as an example, and as an example of good comics). In the book, he parallels these ages of comics with his own life (he was 12 when the Silver Age ended, he was an adolescence at start of Dark Age). He was embarrassed at the ‘cringeworthy’ memoir aspect (memoirs make him sound like he’s 86), but he thought it would mean that people other than comic book fans would read it because it was cached in an acceptable literary format.

Comics are wish fulfilment, in response to question about superheroes being used as propaganda (specifically, Captain America punching Hitler) – this would have been great for soldiers at the time, most of whom would have joined up just so they could punch Hitler on the nose, ignoring the occupied territory and huge army in the way of achieving the goal. He’s sure that Holy Terror will be cathartic for some Americans but it’s not his thing. When asked if he had a final Superman story, Morrison brought up Alan Moore’s Mr Majestic ‘Big Chill’ story (from Wildstorm Spotlight #1), calling it the best thing Moore’s ever done (Morrison would like to write something about it one day), and also thinks it’s the best Superman story. He reckons that if it was drawn by someone like Jim Lee (and not Carlos D’Anda), it would be considered a classic. One answer to a question involved him talking about Socratic Dialogue and then Ronald McDonald and referencing his own conversation with Animal Man in the classic issue where Morrison meets the character. Wonderfully bizarre.

It wasn’t all comic book talk. When talking about the current evolution of human society (we have the database of human knowledge at our fingertips, we are making new connections in a new way now, but we’re too close to it to understand how fast it is happening and what it will do, but it is having an impact), he talked about the phone as an organism that has evolved with us, adapting to our needs – ‘machines don’t want to kill us, they want to fuck us, like we want to fuck them.’ Morrison talked about film: he thinks that in the future, we’ll wonder why we paid Tom Cruise to be the hero in films when we will soon be the heroes in our own entertainment – he thinks everything will be video games 20 years down the line. Saying that, he has just finished writing the script for Barry Sonnenfeld – Dinosaurs Vs Aliens – and really enjoyed it; he laughingly said he wanted to do more – particularly Dinosaurs Vs Quakers. He also talked about some heavy stuff, when talk of how superhero always come back led into how your mum/dad won’t come back to life, and talk of how he’s getting older and how hard it is to see his mother, a strong feminist, not as able to think as she could. He said that he wanted to go the same way as the magician in Captain Marvel’s origin – a concrete block falling on him and crushing him. The phrase that also stuck with me was, ‘Being human is hardcore’, meaning that it’s scary on the small scale. Although, after talking about some heavy stuff to do with human society and progress, he said, ‘I don’t know, I’m not a fucking guru’ with a laugh

It was such a shame that we weren’t allowed to photograph or record – I wanted a transcript just to capture a record of his thoughts on everything. He expressed himself so well and eloquently and passionately. An hour wasn’t enough, as he said when he finished answering the last question, ‘I was enjoying that’ with a smile on his face. He was doing a signing afterwards, but only if you bought a copy of the book – I almost wish I bought hardbacks. The book sounds like it’s going to be amazing, and I can’t wait to read it. Listening to him talk, I was enthused about comic books again and their possibilities, and I wanted to read all Morrison’s books all over again.