Confession: I have never read Will Eisner’s The Spirit. I am aware of Eisner and The Spirit and the Eisner Awards and the influence of Eisner on comic book storytelling; it’s just that I haven’t read the original stories. Even the London library system doesn’t have any collections for me to read. But this is okay – it means I can watch the film with no preconceived notions. I even watched Sin City again to prime myself. Even though the film wasn’t screened for critics in the UK, and the Metacritic rating was low, and it tanked in the USA – I was going in with an open mind.

Turns out I was wrong. But some things you have to learn for yourself. To summarise (because this will be a long ramble): The Spirit isn’t so awful it’s entertaining, but it’s not very good either.

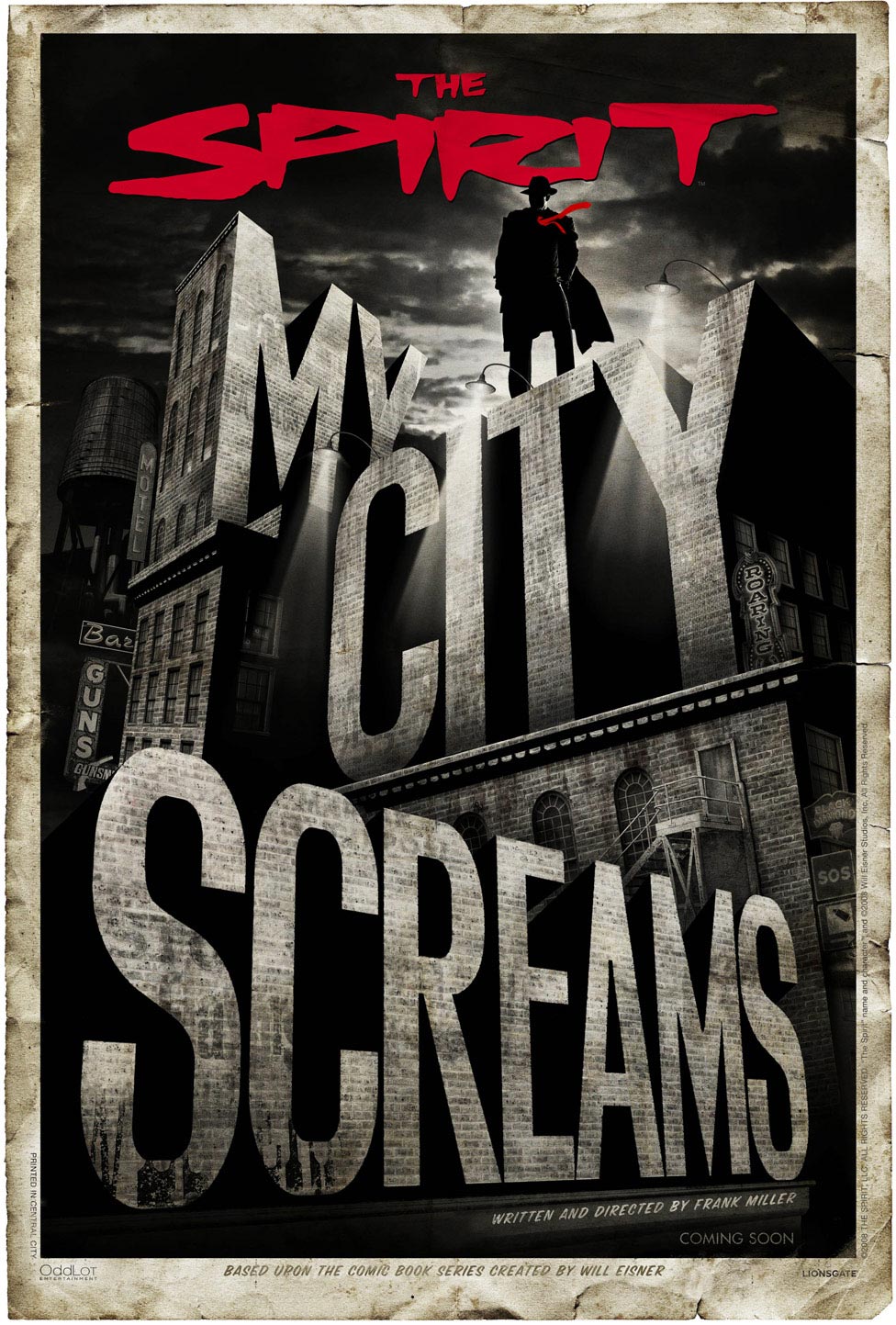

The film sees the Spirit’s nemesis, the Octopus, searching for The Blood of Herakles (which he thinks will make him a god), while Sand Saref (the first love of the Spirit when he was a teenager) returns to Central City to search for the Golden Fleece (from Jason and the Argonauts). And … that’s about it, plot-wise. The film is told in the same style as Sin City, so it is mostly black and white with some colour, as the actors are shot in green screen and the backgrounds filled in digitally. This means that it is constantly snowing when they are outside but no snow settles on the characters or their clothes. Like Sin City, there is some hard-boiled first-person narrative from the Spirit, and people talk as if they are in 1940s pulp novel. Miller wants to have his cake and eat it too when it comes to the time in which the film is set: men wear trench coats and hats while referring to women as ‘dames’ and ‘broads’, the women wear clothes you only see in black and white movies, the vehicles are old-fashioned and an EC horror comic is read at one point yet the presence of mobile phones that can stream video and hi-tech guns suggest we are in the present (and there is the awful, awful piece of dialogue ‘Dead as Star Trek’, which not only puts a specific time frame on the film but also badly anchors the film with pop cultural referencing it doesn’t need).

I’ve been pondering the film and I’ve come to the conclusion that Miller has taken to heart what was said about Sin City the film (‘It was like the comics on the screen’) and used it literally as the basis of the film: this is ACTUALLY a comic book on the screen, rather than a movie in the traditional sense. While watching the film, I could see this as a Frank Miller graphic novel, with all his usual obsessions, that has somehow been financed up to the level of moving pictures. It explains so much. There are shots that look like they are panels from a comic book but look silly on the big screen (such as the close-ups on eyes, particularly the Spirit mask, or a cut to another character in a scene that doesn’t make any sense other than to show they are there, such as a mid-shot of Scarlett Johansson not even reacting to something Samuel L Jackson is saying to the Spirit). The narrative, the flashbacks, the fights all come straight out of a Frank Miller comic book but without the directorial panache required to convert them properly to film. This is the crucial missing link between having Robert Rodriguez in charge of Sin City but allowing Miller co-directing, and Miller going solo: he doesn’t completely know what he is doing, so relies on the things he knows: comic books.

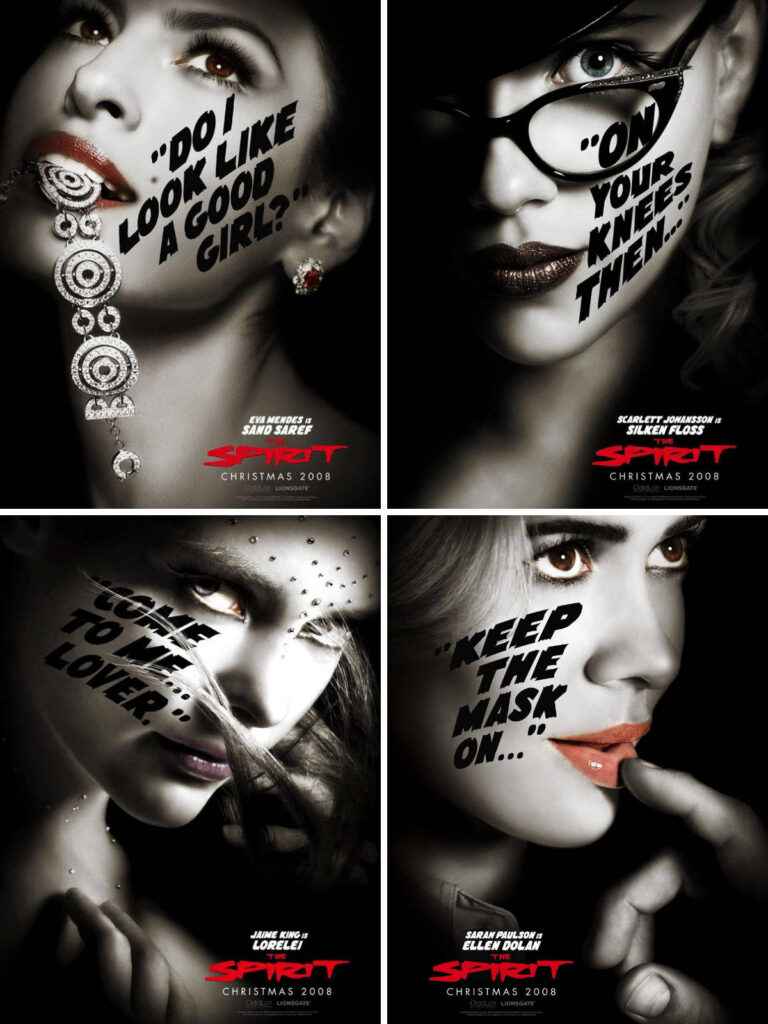

(This lack of directorial experience shows in the different range of acting that appears: Jackson is completely over the top as the Octopus, chewing the scenery as if it was his only source of nourishment; Johansson gives a wooden delivery as Silken Floss, the Octopus’ assistant, at a loss with what she is to do; Dan Lauria, as Commissioner Dolan, seems to be out of a television parody of 1940s noir films; Stana Katic is rather annoying as Morgenstern, a rookie cop who talks with a Noo Yawk accent only heard in old films; I felt sorry for the lovely Paz Vega, as Plaster of Paris, a Spanish woman dressed as a belly dancer doing a French accent for a few short minutes – what was the point of her even being in the film?; I also felt sorry for Jaime King as Lorelei Rox, floating around as a sort special angel of death for policemen, popping up every now and then to say ‘Soon, Spirit’ or something equally pointless; the only people who survive are Sarah Poulson, underused as Dr Ellen Dolan (girlfriend to Denny Colt before he ‘died’ and became the Spirit), and Eva Mendes, as femme fatale Sand Saref, who seems to understand what is expected of her and the role she is playing, although I don’t know how Miller persuaded her to reveal her delightful derrière on screen. At least everyone in Sin City knew they were in an over-the-top hard-boiled noir film.)

(This lack of directorial experience shows in the different range of acting that appears: Jackson is completely over the top as the Octopus, chewing the scenery as if it was his only source of nourishment; Johansson gives a wooden delivery as Silken Floss, the Octopus’ assistant, at a loss with what she is to do; Dan Lauria, as Commissioner Dolan, seems to be out of a television parody of 1940s noir films; Stana Katic is rather annoying as Morgenstern, a rookie cop who talks with a Noo Yawk accent only heard in old films; I felt sorry for the lovely Paz Vega, as Plaster of Paris, a Spanish woman dressed as a belly dancer doing a French accent for a few short minutes – what was the point of her even being in the film?; I also felt sorry for Jaime King as Lorelei Rox, floating around as a sort special angel of death for policemen, popping up every now and then to say ‘Soon, Spirit’ or something equally pointless; the only people who survive are Sarah Poulson, underused as Dr Ellen Dolan (girlfriend to Denny Colt before he ‘died’ and became the Spirit), and Eva Mendes, as femme fatale Sand Saref, who seems to understand what is expected of her and the role she is playing, although I don’t know how Miller persuaded her to reveal her delightful derrière on screen. At least everyone in Sin City knew they were in an over-the-top hard-boiled noir film.)

There are other indicators that this comes from Miller doing it as a comic book first. There are the references to people in the comic book industry: a reference to Dropsie Avenue (the name of a graphic novel by Eisner); Feiffer’s Industrial Salts (Jules Feiffer was a comic book writer and screenwriter, who ghost wrote The Spirit comic book for a while); a young Denny buys a necklace for Saref from Kurtzmann’s (Harvey Kurtzmann, the founding editor of MAD magazine); two characters are called Donenfeld and Liebowitz (named after the two men who founded National Allied Publications, which became DC Comics); and a Ditko’s Speedy Delivery van (after Steve Ditko, co-creator of Dr Strange and Spider-Man, among many, many others). This is cute but works better in comic books.

The other main factor that indicates comic book origins is the presence of specific (to me, at least) references to Miller’s own comic book work: the Spirit runs along a rope between buildings (in some very bad CGI) that echoes Daredevil’s running along cables. Another Daredevil reference seems to be when the Spirit backflips up the side of a building in an impossible fashion, defying laws of physics and anatomy. The Spirit’s obsessive love with the well-being of his city is Miller’s idea for Batman and Gotham City. He has the Noo Yawk rookie cop explain the Elektra complex to Dolan in a very obvious ‘Look at me, I created Elektra in comics!’ moment. Commissioner Dolan peppers his dialogue with enough ‘Goddams’ to almost make you forget how many Miller used in All Star Batman and Robin The Boy Wonder. There are cats in the Spirit’s home (why?) and he is followed around the city by another cat (to whom he talks when he has to explain the flashback to his experiences with the young Sand Saref, a conceit that might work in comics with the use of internal monologue, but sounds really stupid when you see a grown man talking to a cat about his first love), all of which seems to reference the many cats of Catwoman from his Batman: Year One story. There’s even a moment when we first see Poulson where she has a hood to her outfit that makes her look a little like the Virgin Mary, which harks back to Miller’s Daredevil and the whole Catholic thing and his mother becoming a nun (Daredevil’s, not Miller’s). There is a final shoot-out between Octopus and his henchmen and a team of SWAT cops that seems like the cinematic version of the Batman: Year One scene that was lifted for Batman Begins. It’s as if he read about auteurs and thought he should get all his identifying signifiers into his first film.

The end credits have Miller-drawn images that look like storyboards for the film that could have come straight from a Miller comic book of The Spirit, to highlight my point. But there are other aspects of the film itself that stand out as something comic booky rather than cinematic. When we are introduced to Plaster of Paris, the Spirit looks straight to camera to explain who she is and how crazy she is – a thought balloon or internal narration in a comic book would be fine, but this just throws you out of the narrative. The stupidity of the plot – the blood of Herakles will make the Octopus a god? Really? All of this film noir trapping and the macguffin is something that would be laughed at in a comic book. The ‘humour’ in the film is just jarringly unfunny: in the first few minutes, the Octopus smashes a toilet over the Spirit’s head, which he finds hysterically funny. When the Spirit doesn’t laugh, the Octopus says, ‘Come on! Toilets are always funny.’ Maybe they are, but that joke isn’t. There is also the running joke of the stupid, bald cloned henchman with jokey names ending with ‘-os’ on their black t-shirts, saying stupid things and doing things badly. Not only are they annoying to the viewer, they are also annoying to Octopus and Floss, which highlights the irritation and lack of humour. This obviously worked on the page better than on screen.

It’s not just these things that distract. There are some errors of judgement and logic that distract. Why is the Spirit running along rooftops and not using a vehicle when he’s in such a hurry at the beginning of the film? Why does Ellen Dolan not recognise her former boyfriend just because he is wearing a mask? She’s treating him for his injuries on a near daily basis. The linking of the origins of the Spirit and the Octopus and their ability to heal is a misstep, and smacks too much of the first Batman film linking the Batman and the Joker. Having a can of Diet Pepsi placed prominently with the word and logo clearly visible is extremely clunky and a little embarrassing. Why, when the Spirit emerges from the river from nearly dying, is there a dinosaur toy (or model) on the side of the river bank? Is it supposed to symbolise something? Is it saying that the Spirit is a dinosaur in a world that doesn’t have room for his sort of heroism? However, these all pale in comparison with the Nazi-themed scene. Having captured the Spirit, Octopus and Floss have tied him to a dentist chair, with a large Nazi symbol in one corner of the room, and they are both dressed in Nazi uniforms. Why? Don’t ask me. Then, the Octopus does a bizarre speech, while wearing a monocle, which even the Spirit says is boring him senseless – you don’t get to put a tedious bit in your film and then complain about it using one of the characters. It is a failure on the creator’s part and shouldn’t be allowed.

It’s not just these things that distract. There are some errors of judgement and logic that distract. Why is the Spirit running along rooftops and not using a vehicle when he’s in such a hurry at the beginning of the film? Why does Ellen Dolan not recognise her former boyfriend just because he is wearing a mask? She’s treating him for his injuries on a near daily basis. The linking of the origins of the Spirit and the Octopus and their ability to heal is a misstep, and smacks too much of the first Batman film linking the Batman and the Joker. Having a can of Diet Pepsi placed prominently with the word and logo clearly visible is extremely clunky and a little embarrassing. Why, when the Spirit emerges from the river from nearly dying, is there a dinosaur toy (or model) on the side of the river bank? Is it supposed to symbolise something? Is it saying that the Spirit is a dinosaur in a world that doesn’t have room for his sort of heroism? However, these all pale in comparison with the Nazi-themed scene. Having captured the Spirit, Octopus and Floss have tied him to a dentist chair, with a large Nazi symbol in one corner of the room, and they are both dressed in Nazi uniforms. Why? Don’t ask me. Then, the Octopus does a bizarre speech, while wearing a monocle, which even the Spirit says is boring him senseless – you don’t get to put a tedious bit in your film and then complain about it using one of the characters. It is a failure on the creator’s part and shouldn’t be allowed.

I have read opinions from informed sources that Miller hasn’t done a Spirit that channels the source material, aiming for a Miller version of The Spirit (although lamely keeping some of the whimsical tone and humour that was part of the charm of the original). Although I think that Miller misses the point by doing his version, I wouldn’t mind if this was a good film in its own right. It seems that Miller, elevated rapidly to a position of power and wealth in the Hollywood hierarchy that others must be jealous of, has tried to repeat the success of Sin City by taking the opportunity of doing something new to show that he’s got what it takes to make it in Hollywood. If this were the world of comics, we would be wondering why Miller didn’t create his own Spirit-like character if he wanted to do something different to the source material, but it doesn’t work that way in films – a franchise opportunity based on a (slightly) known concept is going to get financed over completely new material. Which is why we get Frank Miller’s Spirit. Unfortunately, Frank Miller’s Spirit isn’t very good – as a film it’s a bit of a mess, it doesn’t really do anything interesting and Miller employs style over substance to provide a disappointing cinematic experience.

Rating: D