I recently read the collected Captain America and Bucky: The Life Story of Bucky Barnes, which was written by Ed Brubaker and Marc Andreyko. Comprising Captain America and Bucky #620–624, it was a perfectly fine story – a well-told tale of how Bucky came to be Cap’s sidekick – but it seemed to lack the spark I got from reading Brubaker’s solo work on Captain America (although, saying that, I didn’t enjoy his Captain America stuff after the Reborn storyline, which I felt was a bit disappointing after his great run on the series – the introduction of the traditional superhero stuff didn’t work for me, whereas the espionage-based stories had been cracking stuff).

But it got me thinking: was it a case of the magic being diluted by the writing partnership?

It’s an inaccurate assessment to say that a single writer provides a purer vision in comic books because a comic book is a collaboration, a combination of words and pictures, between and writer and an artist (and inker and letterer and colourer). However, the vast majority of books tend to be written by a solo writer, mainly due to necessary expediency of the factory method of making comic books (script to pencils to inks to letters to colours) and the sheer amount of books produced monthly in the Anglophone mainstream superhero industry.

So, is co-writing an extension of the factory method, allowing more comic books to be created on schedule? Is it a necessity to allow smooth transition of a creative team on a book? Marvel had a bit of a trend for having the new writer work with the old writer for a few issues before taking over, such as Cullen Bunn on Captain America, Kieron Gillen with Matt Fraction on the X-Men, Rick Remender with Matt Fraction on Punisher War Journal. Or is it a muddle that interferes with the quality of a book?

My initial hypothesis was that having another writer effectively scripting the story notes of another writer leads to a dilution of the former and an imitation by the latter. The original writer is plotting without adding the touches that enhance the story (dialogue, themes, twists) and the second writer is trying to write in the voice of the first writer so there is no noticeable difference. However, when I started to research this theory, I discovered that there were plenty of examples of two writers combining to create good comic books.

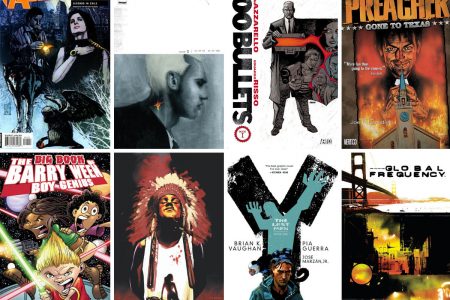

The team of Keith Giffen and JM DeMatteis is an excellent one, even if the duties are more defined, with Giffen as the plotter (and thumbnailer) and DeMatteis as the scripter. Their work on the Justice League, especially at a time when funny superheroes were considered anathema to comic book fans, was a delight and required the different tones of the pair (plus the great art of Kevin Maguire, but you knew that) to produce something that neither could produce on their own. (Although, in full disclosure, I didn’t enjoy Justice League Europe, co-written by Giffen and Gerard Jones.) Giffen worked well with Robert Fleming on the various Ambush Bug series they did together, so Giffen must work fairly well with others; he also worked well with the Bierbaums on the ‘Five Years Later’ incarnation of The Legion of Super-Heroes, as well as The Heckler mini-series. Andreyko co-wrote Torso with Brian Michael Bendis; it’s a good book even if it doesn’t feel strictly like either writer’s voice. The writing partnership of Brubaker and Greg Rucka on Gotham Central was fantastic – the ‘voice’ of the book seemed a synthesis of the two writers and the combined voice was great, even if there was a bit of a split in duties over the night shift and the day shift. Brubaker also co-wrote the excellent The Immortal Iron Fist with Matt Fraction, but he has admitted that he took a back seat on that series.

Then we have the book with four writers – 52, written by Geoff Johns, Grant Morrison, Mark Waid and Greg Rucka (a book I enjoyed) – which is an incredible achievement if only because it was a weekly comic over the course of a single year with four writers. Morrison had previous form for co-writing: he helped to kick-start Mark Millar’s career when they co-wrote the four issues of Swamp Thing before Millar continued a very good run as the singular writer. They also wrote The Flash together for 12 issues, as well as the 10 issues of the unjustly cancelled Aztek The Ultimate Man and the Skrull Kill Krew five-issue mini-series. There are also the many, many Judge Dredd comics that were co-written by John Wagner and Alan Grant, but I’m not sufficiently knowledgeable on examples to provide specific data. A specific example would be Incredible Hercules: co-written by Greg Pak and Fred Van Lente, this was a delightful synthesis of the two writers and a deservedly praised and loved book, which unfortunately didn’t survive the transition from what was effectively a buddy book (Hercules and boy genius Amadeus Cho) to a solo title for Herc. (An aside: subsequently, I prefer van Lente’s solo writing more than Pak’s, but that doesn’t devalue their achievement on Incredible Hercules.)

Although the previous paragraph would suggest that co-writing is good, there are examples that support my initial hypothesis. I loved James Robinson’s Starman, but I always preferred the first half where he was the only writer, before he was joined by David Goyer for the finish. Bendis was co-writer with Jonathan Hickman on the first arc of Secret Warriors, before Hickman took over, but that felt more like Hickman writing from a general idea from Bendis rather than a strict co-writing arrangement, with the added attempt to launch a series with new characters with the Bendis name attached. Bendis scripted the Millar plot for the first arc of the Ultimate Fantastic Four, which wasn’t the best way to start a new version of the flagship Marvel characters and isn’t particularly remembered as a great story. Mark Waid first came to my attention through his work on the Wally West Flash series in the late 1990s; eventually, he would co-write the book with long-time editor on the book, Brian Augustyn, but I never felt the same energy as I got from the first section of the run. I’m a big fan of the work of Warren Ellis, but I didn’t enjoy his showrunner-style Counter-X (X-Man, X-Force and Generation Next), where he plotted the general direction and co-wrote the titles. I enjoyed Buffy the Vampire Slayer on television but stopped reading the comic books, which have a similar approach to the television show with Joss Whedon as showrunner and other writers handling individual arcs.

So, is there a point to all this? It’s not a complete analysis because I’ve only taken into account comic books that I have read. I haven’t assessed writing teams against solo writers to test my hypothesis. There is also the fact that I may be too in love with the auteur theory (usually applied in the even more collaborative medium of cinema) of the individual comic book writer, as I tend to favour comic books for the consistent vision of an author. I think that there’s something more direct in a single author mainlining their story on their own (with an artist) directly into my brain with as little interference as possible.

As with everything, it’s not a black and white area – there are good books by solo writers and good books by writers combining their talents (do I include the Lennon/McCartney-like relationship of Claremont and Byrne on Uncanny X-Men as an example of a good writing team, or was it a more acknowledged collaboration?), but then there are also bad books by solo writers and bad books by writing teams. Just as long as there are good comic books, I shouldn’t worry about it too much.